News Story

This collection begins in late 70s Birmingham, a socially and politically turbulent time. By 1979, the winter of discontent, there were strikes by miners and public sector workers, inflation was through the roof, the government went into melt down, and eventually collapsed. It was no wonder then that the 80s began dispiritedly and remained bleak throughout. Margaret Thatcher became the new leader of a hard right party and their policies felt like a grudge against probably everyone, apart from the elitist No Turning Back Group of hard righters. The 80s followed with yet more strikes, and industries such as mining, ship building, and steel were decimated. A war was also fought against Argentina. Medical hospitals began to face record waiting lists on which many died, while mental and disability hospitals and units were closed, forcing patients into temporary hotel accommodation or shop doorway homelessness. Riots broke out in London, Liverpool, Leeds and Birmingham, and women camped to protest missiles at Greenham.

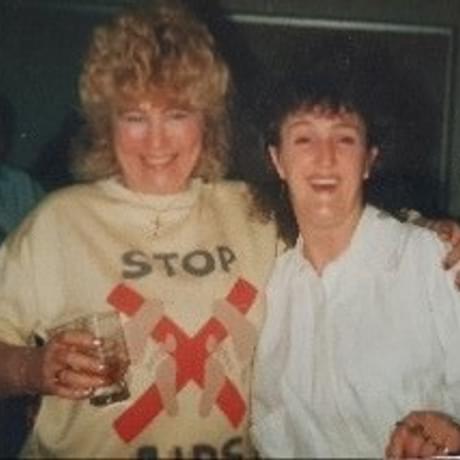

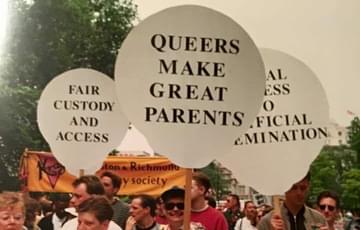

Within this context Thatcher promoted motherland values, healthy family relationships as being the core of society and the only acceptable norm. Her political intention was to stymie and cripple homosexuality. In particular, her government introduced, and parliament passed, what became known as Clause 28 – the scandalous law which prohibited the promotion of homosexuality by local authorities. Did I mention there was also a Gay Plague? Sorry – Aids to you, before you, me or we die of ignorance.

It perhaps goes without saying that the 70s and 80s were homophobic. In fact the police preferred to raid LGBTQ+ pubs and clubs in town rather than protect the queer citizens of the city. On many occasions 30,40, 50 police officers with pointed hats streamed up and down the stairs of these venues shoving people against walls and bars – kicking legs apart to search for … who knows what? Out of town venues weren’t subject to the same raids, but instead often presented a different danger to get home.

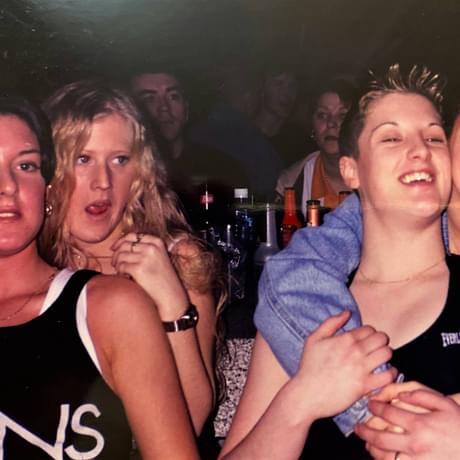

The community was comprised of pubs, parties, and clubs and within these settings were different groups of women. There was The Greyhound, The Nightingale, The Jug, The Viking, The Windmill, The Jester, The Old Mo, The Malt Shovel, The Victoria and then later, Peacocks. One-nighters happened at The Matador and The Mermaid and there was a famous night club spot called Legends, and the Birmingham Lesbian and Gay Centre. Not all these venues were exclusively queer.

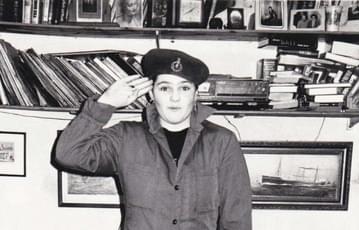

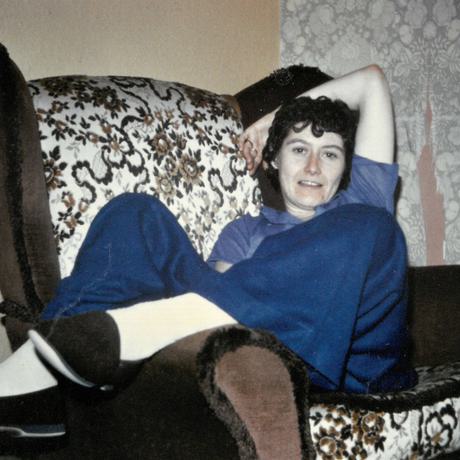

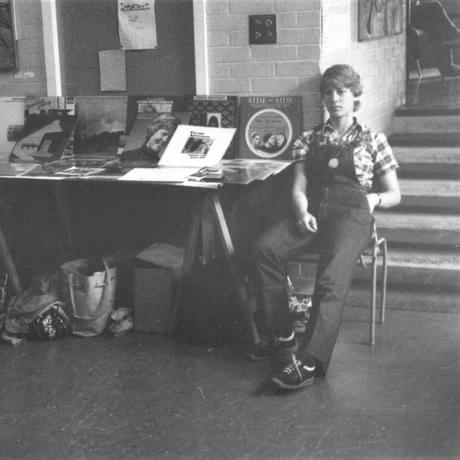

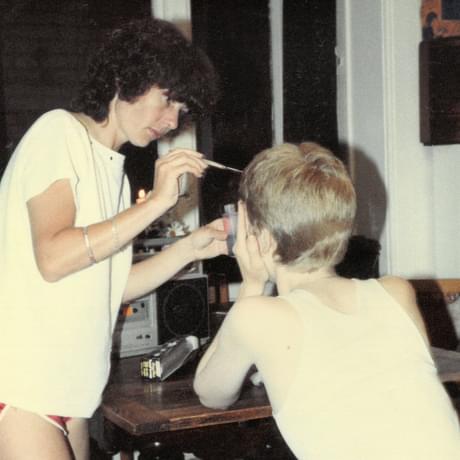

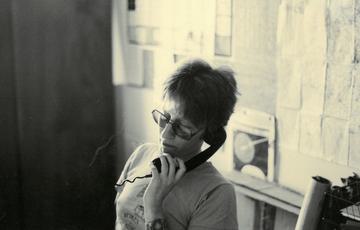

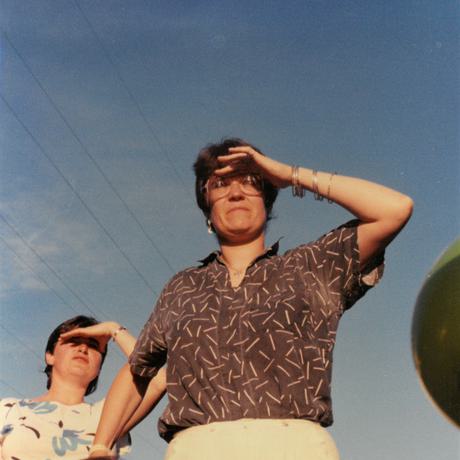

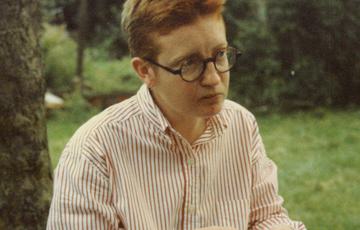

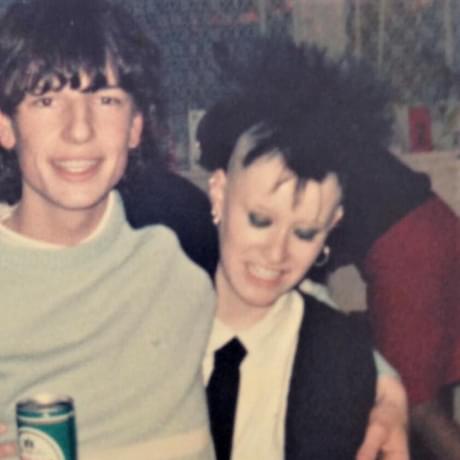

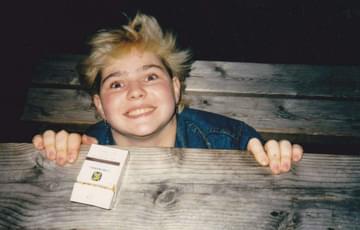

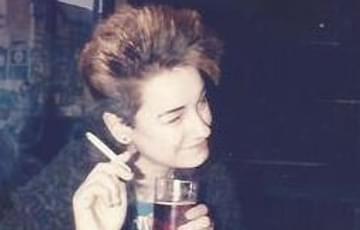

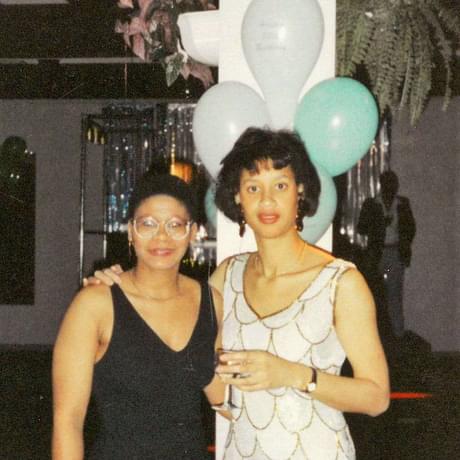

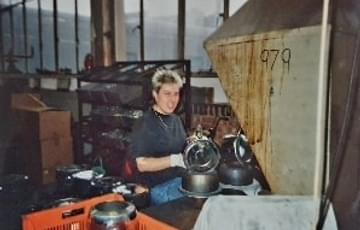

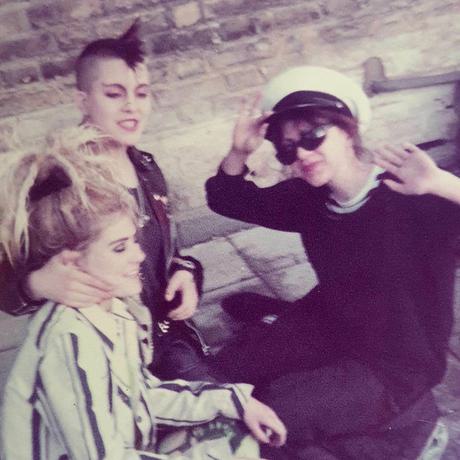

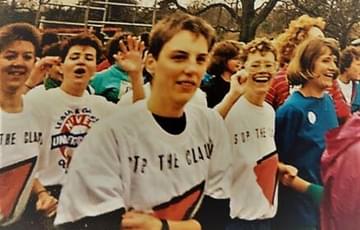

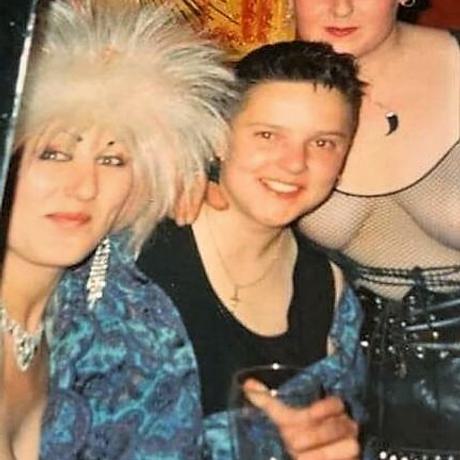

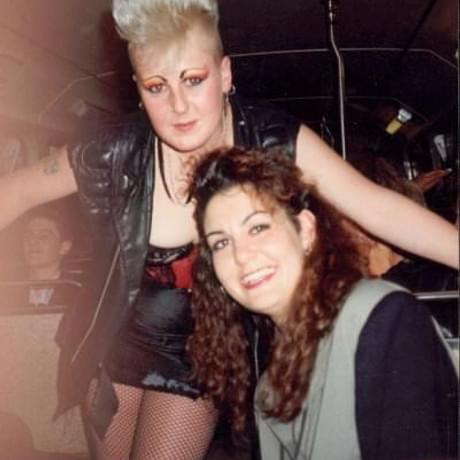

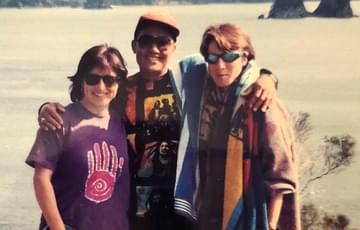

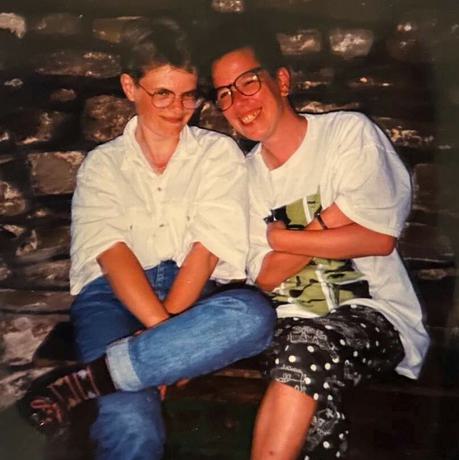

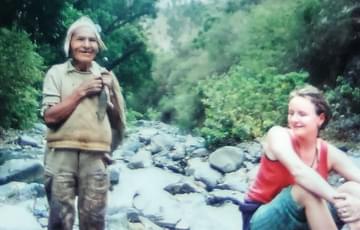

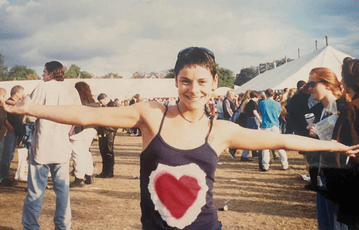

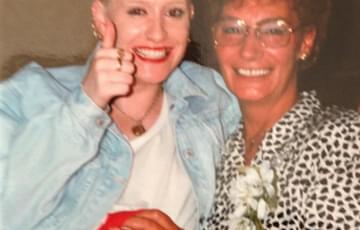

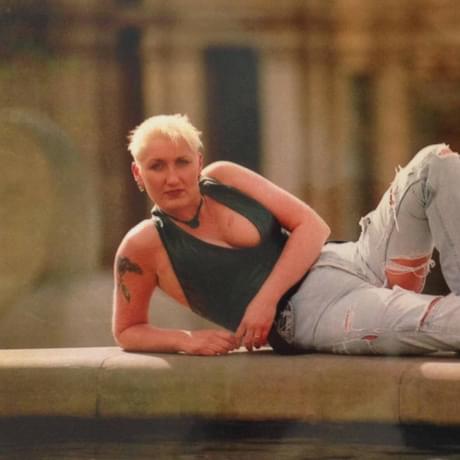

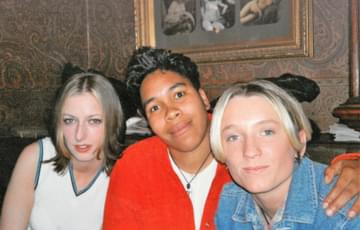

The photos that follow are of Birmingham queer women and to clarify, queer isn’t a slur. It’s an inclusive term used to encapsulate a whole community, and in this case varied female identities: lesbians, bisexuals, trans, asexuals, intersexes and allies. Queer is about being different from the norm. The photos show that identities were not always obvious or overt and they’re a record of authentic queer Birmingham histories that could otherwise have been lost, hidden, or simply discarded at death.

This collection is important for two reasons. Typically, a lack of visibility has led to myths that queer people either didn’t really exist years ago, or if they did, they lived sad, perhaps tragic lives without fun, care, or love. This collection is evidence that counters those ideas.

Additionally, this collection is a history of real women that lived in Birmingham and were part of changing perceptions of the LGBTQ+ community. It begins before clause 28, the 2010 equality act, the declassification of LGBT as a mental illness, rights to serve in the forces, adoption rights and the rights to civil partnership and later marriage. These women were out when the biggest shifts to their rights and future generations were in the balance. Thus, they should be remembered as part of a visible path towards positive change.

Women primarily come from 3 camps of Brum queer women (not the only camps). They’re the scene town women, alternative scene women and Moseley/Balsall Heath/Kings Heath women. Four Birmingham legends: Patti Bell, Lesley Woods, Chrissy van Dyke and Lisa Wallace also donated photos as they wanted to be included in this history. Patti was a fashion designer, Lesley was from the band Au Pairs, Chrissy, the band Plutonik and Lisa was of Big Brother 10 fame.

Most photos are snaps that were taken in clubs, bars and sometimes outings or protests, or at London Prides, as it was in these spaces that queer communities could exist freely. However, as you will also see, women had holidays, travelled, and had house and garden parties. What you don’t see is that taking photos was something of a luxury, money was often tight, and photography was expensive.

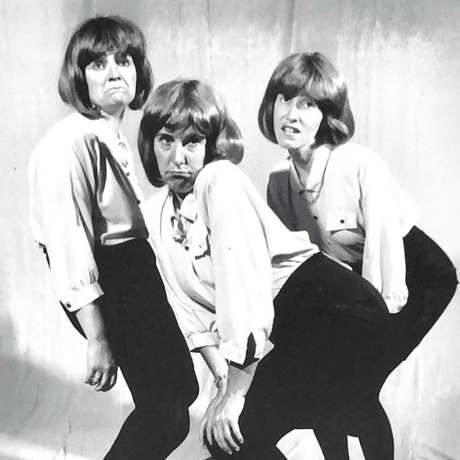

Women and Theatre have also kindly donated photos from their archive featuring Polly Wright, Jo Broadwood and ally, Janice Connolly, aka Barbara Nice. This theatre company produces and performs engaging and dynamic theatre about issues that matter and has done since 1983. Productions have taken on subjects around sexuality, HIV, relationships, equality, aging, and class, either in play or monologue forms and the range has been the fullest from serious drama to light-hearted comedy.

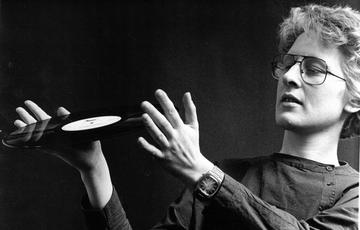

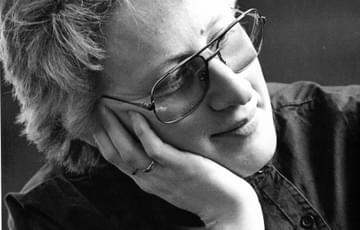

Caroline Hutton donated her Women's Revolutions Per Minute (WRPM) publicity photos. WRPM was a Birmingham based feminist women’s music distributor. It distributed feminist cassettes, records, cds and books nationally and internationally. WRPM’s archive is already the subject of academic studies in music, gender and sexuality as it was a leading force behind feminist music in the UK in from the late 70s until 1999. More information can be found about WRPM in the Goldsmiths University Library. Photographer Rhonda Wilson took these publicity shots, and this collaboration between Wilson and WRPM was very much about women with shared values and politics assisting each other in business.

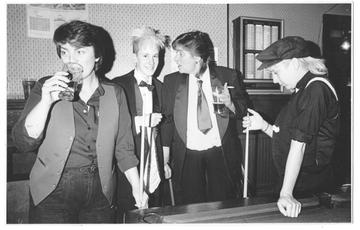

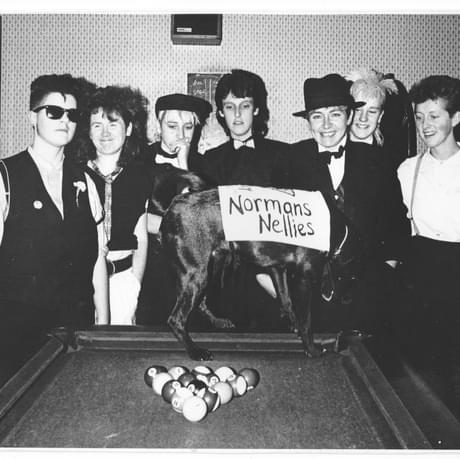

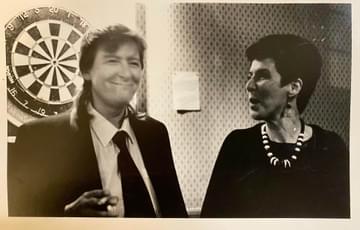

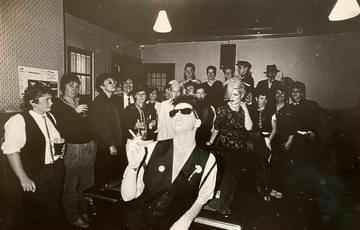

Rhonda Wilson also took the pool players’ photographs and it’s with thanks to her husband John McQueen that her photographs are featured in this collection as he granted permission to use them. Rhonda was a great photographer and an important ally of the lesbian and queer community. She was an exceptionally talented photographer and activist who worked tirelessly promoting equality and opportunity in everything she did. The pool players shots of hers were of LBTQ+ women who frequented pubs in Moseley and Balsall Heath in the late 80s and while they’re slightly dressed up for the shoot, Rhonda’s theme was about visibility, stereotypes and authenticity, while also having a good laugh. What’s also notable about the theme of her photos is that the same themes and styles have resonated throughout time within queer communities.

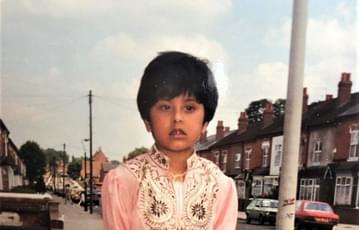

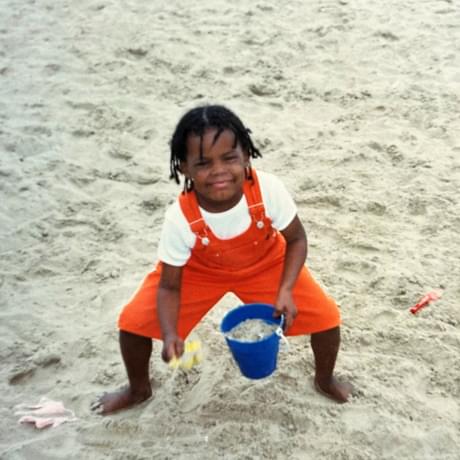

At the end of Rhonda’s photos there is a child in pink, who is artist and activist Saima Razzaq and this marks the end of the 80s. Similarly, the end of the 90s is marked by a child who is a current queer scene DJ, Soriah Lewin. The very last photo is of Ginger Baxter. These photos are to acknowledge the lack of diversity in this collection: ethnic, disabled and elders. Birmingham’s LGBTQ+ scenes in the 80s and 90s were mostly white, able bodied and under 40. Which is not to say that ethnic, disabled and elder communities weren’t LGBTQ+. Rather, they were not visible on these scenes and subsequently have been very difficult to contact to encourage project participation.

The photos run in an approximate time order from 1977 until the end of the 1999.

Lastly, there were some key helpers in this project. They were Nova Bartlett, Marianne Skelcher, Ginger Baxter, Janet Watts, Sandria Allwood and Saima Razzaq. Combined, these women phoned, hassled and harangued for donations. My greatest helpers were Hilli Fletcher and Caroline Hutton as they relentlessly scouted down people and photos and made me lovely cups of tea. My biggest supporter though was my partner who patiently listened, watched and believed.

I hope you enjoy what follows.

Sarah Dolman: artist, writer and educator.