News Story

Our museum collection contains over a million objects, including an extensive oral history collection. These collections give a view of life, work and politics frozen in the moment they were recorded. But what can oral histories offer looking forward? Drawing on Birmingham Museums Trusts’ collection, my project positions oral histories as a valuable community asset for understanding health in the city.

Food is everywhere. It dictates our mood, it shapes our working day, it contains nutrients vital to the growth, repair and maintenance of body tissues and gives us energy to perform our daily tasks. It also acts as a signifier for who we are - the common phrase ‘you are what you eat’ first documented in 1826 refers to the notion that in order to be healthy, you must eat nutritional food. It has since evolved to encompass more than nutrition; food acts as a marker for economic status, social norms and cultural identity, and is deeply connected with a sense of self.

This oral history collection gives an insight into the experience of food and drink in the city from the 1900s, spanning to the ‘present’ day of 1984. The large sociocultural changes are documented in this collection; major wars and rationing, international migration, technological advancements, all through the lens of food. The more everyday nuanced aspects of food are also explored, with individuals making connections between food and particular places in Birmingham, documenting changing food patterns and the impact of fast food culture, the rise and decline of markets and describing the process of learning how to cook. The collection gives a snapshot of culture and the food landscape in the 1980s, frozen in time.

See below some of the objects in our collection relating to these oral histories:

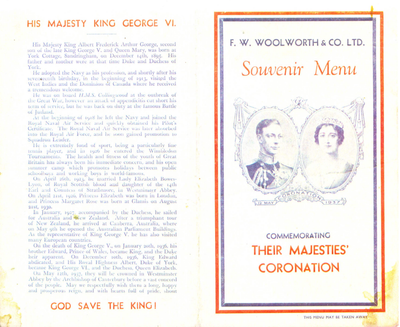

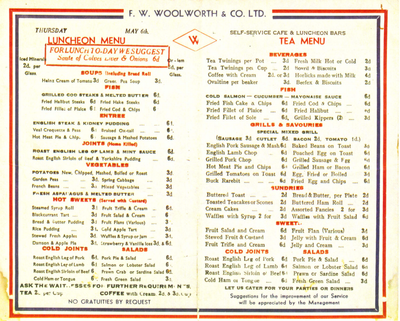

This menu from the coronation of George VI and his wife on the 12th of May 1937, as King and Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth, and Emperor and Empress consort of India. Coronation food reflects the tastes of the era, using ingredients and equipment popular at the time. Some infamous foods we can thank coronations for include Victoria sponge (invented for Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1938), coronation chicken (invented for Queen Elizabeth II in January 1953) and the Battenburg cake (first baked to commemorate the marriage of Prince Louis of Battenberg and Princess Victoria). The donor of this menu worked in Woolworths restaurant, and would have served this lunch spread.

This potato cart was donated by Philip Allonzo in 1971, which he used to wheel around by hand near the rag market, Ladywood, up and down Navigation Street, and at fairs near Cannon Hill park and Aston Hall. The streets would have been echoing with the cries of the sellers, many of whom were Italian migrants.

Given the mundane yet extraordinary nature of food, it is necessary to draw from many different sources to understand this topic and the food choices made by individuals in the city everyday. Birmingham has an ambitious food strategy, which offers an approach grounded in community need, considering the entire food system with a holistic view of health. Exploring this strategy alongside the oral history collection allows an opportunity to see how food culture has changed, and the place of heritage within contemporary policy and debates. Whilst we might not be dipping bread in lard anymore, our food practices are passed down generationally, and many of our resourceful, cultural and social experiences of food remain the same today. Drawing on oral histories forefronts the lived experiences of people and centres people as data sources in themselves, bringing a nuance to the often top down history record. Because of this, they can offer scope of the wider sociocultural determinants of health, and also the visceral, everyday experience of health and wellbeing.

By Sophie Beckett (Public Health Research Officer)