News Story

Over the past year, due to essential electrical works, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG) has moved 36,000 items from its 40 galleries but one significant artwork has remained: Sir Jacob Epstein’s Lucifer.

The winged bronze oversized figure is Epstein’s depiction of the archangel Lucifer and was inspired by the renowned sculptor’s fascination with John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost (1667). The 11ft (3.36m) 2-tonne (2,000kg) statue took five years to create, was completed in 1945 and has been housed predominately in BMAG’s Round Room since 1947.

There, at the heart of the museum, Lucifer has seemingly stood unmoved, tall and firm, as a custodian of the collection and as an affirmation of the artist’s genius and its value to the museum.

However, that’s not quite the case as not only did Lucifer have a tough time finding a home before its arrival at BMAG, the sculpture’s fate within the museum has been up for discussion on more than one occasion and has spent some time on loan, in storage and at one point displayed in the Edwardian Tea Rooms and what is today the gift shop.

Most recently Lucifer’s future was in the hands of six young people of colour from We Don’t Settle – which promotes untold stories and amplifies unheard voices through arts, culture and heritage – who had joined up with Birmingham Museums Trust to reimagine BMAG’s Round Room as it was emptied of its artworks.

This resulted in the We Are Birmingham exhibition – reflecting the people of Birmingham – launched in April as part of a partial re-opening of BMAG in conjunction with the Commonwealth Games’ Birmingham 2022 Festival.

We are Birmingham

“There were lots of discussions about Lucifer and we had the option to move the sculpture,” says Emalee Beddoes-Davis, Curator (Modern & Contemporary Art).

“However, quite quickly into working with the activators it became clear that they loved that it has this iconic status in the room, it’s an amazing looking object and it also has two unconventional stories behind it that felt fitting.”

The first being that it has a non-binary body – the head is sculpted in the likeness of a woman that Epstein used to sculpt quite often, Sunita, but the body very physically male.

“That feels relevant to people today because there’s a lot more openness and understanding of non-binary people and non-binary bodies.”

The We Don’t Settle activators also liked the story of it being a displaced object that upon its arrival at BMAG was displayed as a much-appreciated centrepiece, although Beddoes-Davis does say she receives semi-frequent complaints it being blasphemous.

Rejected - then finding a home in Birmingham

Before being gifted to BMAG, Lucifer was exhibited for the first time in 1945 at Leicester Galleries, Epstein's primary dealer.

However, to his surprise it remained unsold until 1946 when it was bought by Professor Arnold Lawrence for £4,000 who, along with his famous brother TE Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), was a great admirer of Epstein’s work.

Lucifer was then offered for display at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (where Prof Lawrence resided) and to his astonishment was rejected. Two further offers to the V&A and The Tate were also declined.

The chairman of the Tate said at the time that the Trustees: “Did not like it sufficiently to include it in the Gallery. The Trustees have no quarrel with Epstein, and we already have several pieces of his work in the Tate … We should prefer to have his Madonna and Child.”

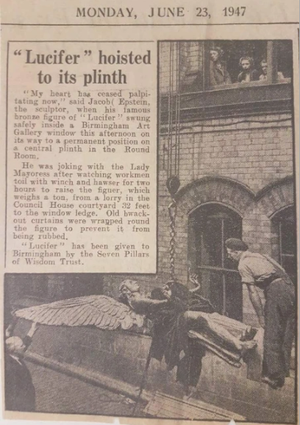

This led to much speculation and press coverage, which in turn led to regional museums and galleries showing an interest in the biblical bronze sculpture. BMAG became the preferred location for the statue, which was gifted to the museum by the artist and the Seven Pillars of Wisdom Trust in 1947 and installed in the Round Room.

Epstein said about the choice of BMAG: “I was visited by the Lord Mayor of Birmingham [Albert Frederick Bradbeer] and the director of the Art Gallery, Mr Trenchard Cox, who [said] that Birmingham should be honoured with the gift. I was very moved by their enthusiasm.”

The statue was delivered to BMAG on 23 June and unveiled to the public two days later. When it arrived at the museum it was too large to fit through the main doors and was hoisted through a window, which took two hours with Epstein in attendance.

Jacob Epstein

Born in 1880, Epstein was raised in New York and was from a Jewish family, the third of eight children. He developed a deep knowledge of Judaism throughout his life and continued to read the Old Testament and subsequently religion features in much of his work.

Epstein became a British subject in 1911, where he was regarded by some to be the country’s greatest sculptor of the time (he was knighted in 1954 five years before his death) with works such as Oscar Wilde Memorial – Père Lachaise Cemetery (1911-12), many busts including the Head of Albert Einstein (1933) and St Michael’s Victory over the Devil – Coventry Cathedral (1958).

He considered Lucifer one of his most important works. His intention was to portray the archangel Lucifer, the bringer of light (Lucifer meaning light-bearer) as the most beautiful of Angels, before his rebellion and fall from heaven.

In her book, Rebel Angel: Sculpture and Drawings by Sir Jacob Epstein, 1880-1953 (Published 1980), Evelyn Silber says: “His choice of the epic Miltonic theme was in keeping with his self-image as a sculpture in the great European tradition. Though almost unprecedented in sculpture, Paradise Lost was a popular theme with 18th and 19th century English artists, especially Fuseli, Blake, Romney and John Martin.”

In 1952 Tate held retrospective exhibition of Epstein’s work with Lucifer as a major component. Life magazine pointed out in a November 1952 feature headlined ‘A Spurned Sculptor Triumphs’ that the London gallery’s exhibition was vindication of the artist’s importance and mentioned that Epstein had labelled the Tate’s Trustees ‘a lot of nincompoops’ for their rejection of the statue as a gift.

Public outcry over proposed more

Nearly a decade later Lucifer was once again on the move, this time to be displayed at Edinburgh’s Waverley Market from August – September 1961 in an exhibition titled Epstein, organised by the Edinburgh Festival Society.

While he was away, a proposal was made by BMAG’s Committee for Lucifer to be moved to Cannon Hill Park but a public outcry forced the plans to be shelved.

The Birmingham Post reported in January 1962 that Councillor Margaret Cooke, chairman of the committee, said they had requested director Mary Woodall to keep Lucifer in the museum after overwhelming public condemnation of the plans.

“We felt that we must have some regard to this weight of public opinion and reconsidered the whole matter,” she said adding it was a pity the statue couldn’t be placed in the park to be seen “at such advantage, as in many European cities”.

The sculpture remained in storage while these deliberations were made with The Post saying: “His return to Birmingham [from Edinburgh] has been a well-kept secret.”

Following these travels Lucifer spent a further two decades at home in the Round Room as the gallery was redecorated and further populated with high-profile works of art until, in the 1990s, the sculpture was relocated to the Edwardian Tea Rooms, and then in 1992 to the coin gallery, now the gift shop, before returning to the its more-familiar plinth in 2006.

Now Lucifer will remain on display in the Round Room until at least October 2022 when the current exhibitions are dismantled and the maintenance work continues – and storage awaits – but will the fallen angel be allowed to spread its wings in public again? And will it be in the Round Room? Only time, and maybe another public outcry, will tell.