News Story

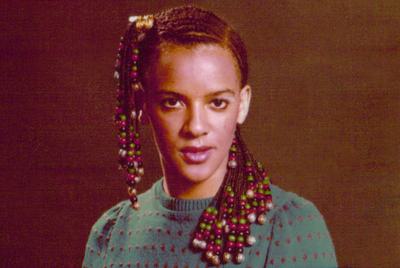

It’s funny how something you created at the start of your career, something you thought was long forgotten suddenly finds a new lease of life! That’s what’s happened to my first documentary, African Oasis, made in 1982.

African Oasis has been screened by Vivid Projects and Midlands Arts Centre cinema several times over the past few years and in 2019 Birmingham Museums Trust acquired my very first trilogy of films (Mirror Mirror 1980, Sweet Chariot 1981, African Oasis 1982) to be part of the city’s permanent collection.

All three films were made with arts grants and produced through the newly formed Birmingham Film Workshop. Roger Shannon was its founding lead and produced African Oasis. Later ‘Video’ was added to the Workshop’s name – a sign that new technology was on its way which would make filmmaking hugely accessible to a wider community and transform the way stories were told.

BFVW was set up in December 1979 to stimulate independent film activity in the region; part of a national movement to respond to a need for alternative voices on race, gender and class to be heard.

For me becoming involved in this movement was a political awakening. I had been in Britain three years by then, but I had been tucked away at the Birmingham School of Photography. The School was very white and very male. I made a lot of white friends and I was never made to feel an outsider.

Having come from Delhi I was surprised at the lack of integration I had noticed amongst the Asian community. My first short fiction film, Mirror Mirror, was a comment on that divide. I recognised later that this isolation was not self-inflicted, that it was mostly due to the host white community not encouraging such integration to take place.

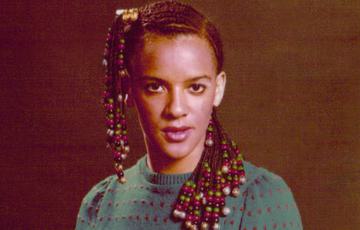

Then, through BFVW, I came into contact with the Handsworth Cultural Centre, its many users and its Director, Bob Ramdhanie (with whom I still collaborate). A whole new world opened up for me. I encountered the African and Caribbean community for the first time in any meaningful way. It was a culture I knew nothing about – and I was captivated. Out of that relationship and workshops held there, came a second short fiction film, Sweet Chariot. Culture, identity and race were now my central focus and a year later came African Oasis, a documentary about the Cultural Centre itself.

In 1985 my brother Sunandan and I set up our own production company (Endboard Productions) and our first few films – Language is the Key featuring poet Benjamin Zephaniah and Silver Shine profiling local jazz legend Andy Hamilton all had race and culture at their core.

As we entered the world of television we encountered a different form of racism. As Asian producers we were routinely shunted off to Channel 4’s multicultural commissioning department. It was as if we were incapable of telling more universal stories. But we were determined to make it in mainstream television. Fortunately, there were some forward thinking, right-minded white commissioners who liked our ideas and did commission us. We ended up making documentaries and telling stories from many different parts of the world and picking up some awards along the way.

We did however engage with and win commissions from the Asian Programmes Unit (APU) at the BBC once that was set up and Sunandan also became a Series Producers there for three years. In time both the multicultural dept at C4 and the APU were disbanded.

This year Channel 5 announced development funding for a range of production companies owned and run by minority ethnic producers. The BBC has ringfenced £100m in production funding to increase diversity on its channels. The fact that broadcasters are still having to take such initiatives in 2020 says a lot in itself.

Here’s an interesting read about racism within the BBC from someone who was there on the inside: I was on a British TV diversity scheme – and saw why they don't change anything by Tabasam Begum.

I do believe that attitudes towards race generally have changed a lot since those early days of the 80s. But now and then, all it takes is a spark, and racism rears its ugly head again and you wonder if anything has changed. African Oasis feels just as relevant today as it did then.