News Story

Standing on the slope of Bennetts Hill, in city centre Birmingham, is The Briar Rose. It’s a pub with history; art history, in fact. Upon first encountering it, I wondered why this Wetherspoons had been given such a romantic name. It wasn’t until a few weeks later that I noticed, fixed rather high up, on a wall opposite, a blue plaque, providing an important clue with its simple inscription:

‘SIR EDWARD BURNE-JONES 1833-1898

Artist born in a house on this site.’

11 Bennetts Hill was once been the home of the hugely influential, Pre-Raphaelite painter. Previously, I’d had no idea he came from the city. But, delving into his story, I found out just how profound and lasting an impact Burne-Jones’ upbringing in Birmingham had on his enchanting art, which the pub was proudly paying tribute to.

Burne-Jones was born and brought up in Birmingham, where his father worked as a frame maker on Bennetts Hill. However, explosive industrial growth within the town meant that artisanal crafts were being replaced by mass produced products, and makers by machines. Even as a boy, and perhaps because of his father’s profession, Burne-Jones rejected the Victorians’ industrial ideals and increased focus on materiality.

Attending King Edward’s School, Burne-Jones first developed a love of classical mythology, ancient civilizations, poetry and art. Between 1848 and 1852, he then studied at the progressive Birmingham School of Art, a significant centre for the Arts and Crafts Movement. Members, including Birmingham’s Joseph Southall, Arthur Gaskin and Georgie Gaskin, critiqued the damaging effects of industrialisation and mass-made products, favouring the decorative arts and the handmade.

While studying Theology at the University of Oxford, Burne-Jones became close friends with a leading Arts and Crafts designer, William Morris. Similarly, Morris shared a love of literature, romanticism, myth and fairy tale. Together with a small group of Burne-Jones’ friends from Birmingham, known as the Birmingham Set, these young men formed a close and intimate society, which they called “The Brotherhood”.

Disenchanted with the academic approach to painting, which was being taught at that time by the Royal Academy of Arts in London, these artists were strongly influenced by an earlier group of painters, The Pre-Raphaelites. Like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, they wanted to modernise art, while also advocating a return to the simplicity and sincerity of subject and style found in an earlier age, pre-Raphael, from which the movement took its name.

Burne-Jones began to adopt their style, while drawing on his classical education in Birmingham, to bring imaginary worlds to life in his paintings. He also enjoyed reading Romantic poetry by contemporaries including Byron, Keats, Shelley and Tennyson. The Romantic poets were fascinated by myth and fairy tale, and Tennyson’s 1842 poem, ‘The Day-Dream’ partly inspired one of Burne-Jones’s greatest artistic accomplishments, after which ‘The Briar Rose’ is named.

Between 1885 and 1890, Burne-Jones worked on four enormous paintings – ‘The Briar Wood’, ‘The Council Chamber’, ‘The Garden Court’ and ‘The Rose Bower’. Burne-Jones deliberately chose themes and stories that could speak to any audience, including the working classes, with this seminal series, titled ‘The Legend of the Briar Rose’.

Taking inspiration from the traditional 'Sleeping Beauty' tale, told by eighteenth century writer Charles Perrault in his ‘Contes du Temps Passé’, as well as from Tennyson’s poem, Burne-Jones chose to focus on a single moment from the famous story: the brave prince, having battled through the briar wood, comes upon the bewitched court of sleeping knights, attendants and the princess, he is to awake with a kiss, all frozen in time in a medieval dream world.

At Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery are seven studies for the ‘The Garden Court’ panel, each depicting a weaver, having fallen asleep at their loom; some have their hands poised mid-air, paused in the act of making. These figures, presented before a backdrop of arched rose bushes and patterned leaves, are highly symbolic, personifying those handmade arts and crafts, which Burne-Jones honoured in the face of encroaching industrialisation.

Burne-Jones again celebrated transformative states in a series of four paintings, ‘Pygmalion and the Image’, 1878, which illustrate Ovid's narrative poem, ‘Metamorphoses’. His paintings represent the sculptor Pygmalion, who has fallen in love with a beautiful statue he has carved. Naming her Galatea, and answering his prayers, the goddess Venus brings the figure to life for the artist.

Awakening is a theme that emerges again and again in the work of Burne-Jones, reflecting his interest in the notion of awakening from out of the darkness of the Victorian age, and escape into fantasy. As he once revealed: “I mean by a picture a beautiful romantic dream of something that never was, never will be – in a light better than any light that ever shone – in a land no one can define, or remember, only desire”.

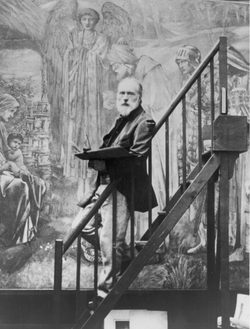

In this series, he also appears to be reflecting on role of the individual artist, surrounded by tools in his studio, to show just how much work has gone into the sculpture, revering, once again, the handmade. It echoes a photograph of Edward Burne-Jones at work, on another masterpiece, ‘The Star of Bethlehem’, 1890. One of the largest watercolour paintings in the world, created at the tapestry-scale of 8-12ft, it presents the Nativity scene. But in this magical version, Mary appears as a Pre-Raphaelite muse, surrounded by flowers, in her long, flowing gown, and accompanied by angels.

Alongside painting, Burne-Jones was exceptionally skilled in a variety of crafts, much like his frame-maker father, and designed ceramic tiles, book illustrations, jewellery, tapestries and mosaics. Working closely with William Morris, he was a founding partner in Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Company, through which he was heavily involved in the rejuvenation of the tradition of stained-glass art in Britain, including his glorious windows at Birmingham Cathedral.

A leading figure in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Burne-Jones rose to both national and international prominence during his lifetime. But it was certainly Birmingham which made him, and it was his allegiances within, as well as reaction to, the city which spurned him on. In the face of rapid industrialisation, the artist created an alternative existence of dreamy enchantment, myth and beauty, which influenced the young J. R. R. Tolkien, another Brummie inspired by his early life in Middle England.

Today, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery houses the largest collection of artworks by Burne-Jones in the world. While it undergoes renovations, and Burne-Jones’ masterpieces are not yet on display, you can still see his divine stained glass windows at the Cathedral Church of St Philip. After visiting, if you fancy a drink, the Briar Rose is waiting for you on Bennetts Hill.

Read more Birmingham Stories